Decoding the Sir Creek Issue: Why This 96-Km Stretch Still Matters

The Sir Creek dispute remains one of the least discussed yet most complex boundary issues between India and Pakistan. This article breaks down its history, geography, and strategic importance — explaining why a 96-km stretch of marshland continues to shape diplomatic and maritime relations in the Arabian Sea.

Pratik Saxena

11/11/20254 min read

Sir Creek: The Marshland That Divides Two Nations

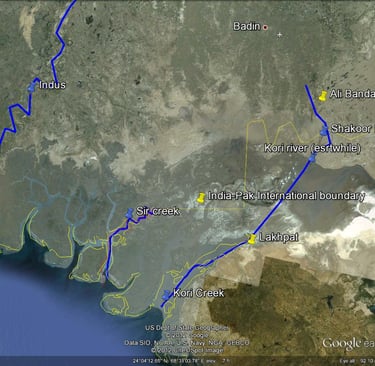

Sir Creek is a 96-kilometre-long tidal estuary in the Rann of Kutch that separates India’s Gujarat from Pakistan’s Sindh province. On the map it looks insignificant — a narrow, shifting waterway cutting through salt marshes — yet it represents one of South Asia’s most enduring border disputes. The creek’s channels change course with every monsoon, its banks are soft and unstable, and no permanent fencing exists. What seems like a forgotten swamp is, in fact, a zone that shapes maritime boundaries, national security, and regional strategy for both India and Pakistan.

A Dispute Rooted in Colonial Confusion

The origin of the Sir Creek dispute lies in a 1914 resolution between the Government of Bombay and the Sindh Division, which was then part of British India. That agreement attempted to define the boundary between Sindh and the princely state of Kutch. One clause placed the boundary on the eastern bank of the creek, while another mentioned the thalweg principle — meaning the border should follow the mid-channel of the navigable waterway.

When India and Pakistan were born in 1947, Kutch went to India and Sindh to Pakistan, leaving Sir Creek ambiguous. After the 1965 war, an international tribunal demarcated most of the Rann of Kutch boundary but deliberately left this stretch unsettled. Over the decades, the two countries have continued to interpret the same colonial documents differently, turning this marshland into a quiet flashpoint.

Why Sir Creek Matters

At the heart of the issue lies maritime entitlement. The exact location of the land boundary determines where the sea boundary — and therefore the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) — begins. A small shift on land could translate into thousands of square kilometres of ocean rights.

For India, keeping the boundary through the creek’s mid-channel upholds international law and secures its western coastline. It also protects vital fishing grounds, potential oil and gas deposits beneath the seabed, and approaches to its key ports in Gujarat. For Pakistan, claiming the entire creek by defining the border along its eastern bank would push its maritime boundary further east, expanding its EEZ and giving it access to richer marine resources.

Beyond resources, the area has strategic value. The creek opens into the Arabian Sea near Pakistan’s Karachi coast — a critical naval hub — and lies close to India’s forward military bases in Gujarat. Control over this zone affects coastal surveillance, infiltration routes, and maritime security.

India’s and Pakistan’s Positions

Pakistan maintains that the boundary lies on the eastern bank, giving it ownership of the entire creek. It bases this on selective interpretation of the 1914 resolution. India rejects that view, arguing that the thalweg principle — accepted worldwide for navigable waterways — places the border down the middle of the creek. British-era maps and mid-channel pillars from 1924–25 support India’s stance.

From India’s perspective, Pakistan’s claim is inconsistent and opportunistic. The 1914 document itself references the mid-channel rule, yet Islamabad chooses to ignore it. By pressing its interpretation, Pakistan aims to expand its maritime claim eastward and secure a larger slice of the Arabian Sea. New Delhi considers this both legally weak and strategically unacceptable.

The Current Military Situation

In recent years, Sir Creek has transformed from a diplomatic dispute into a militarised zone of vigilance. The absence of a physical border and the terrain’s porous nature make it ideal for infiltration, smuggling, and illegal fishing. Both nations have therefore increased military activity and surveillance in the area.

On the Indian side, the Border Security Force maintains floating border outposts and amphibious patrols equipped with night-vision and thermal-imaging devices. The Indian Navy and Coast Guard coordinate closely with the BSF to monitor the adjoining waters, using radar stations and maritime drones to detect intrusions. The Indian Armed Forces regularly conduct shallow-water drills and joint operations — such as Exercise Trishul and Brahma Shira — that include amphibious manoeuvres in the Sir Creek sector. These exercises demonstrate India’s preparedness for both defensive and offensive contingencies in the littoral zone.

Pakistan, meanwhile, has increased the presence of its marines and coastal defence units in Sindh. New radar sites and air-defence positions have been reported along its shoreline. The Pakistan Navy frequently conducts small-boat patrols in the creeks and estuaries leading to Karachi. Although both nations avoid direct confrontation, the proximity of their patrols means the risk of accidental escalation remains high.

The situation escalated rhetorically in October 2025 when India’s Defence Minister warned that any Pakistani “misadventure” in Sir Creek would invite a response that could “change both history and geography.” The statement reflected India’s determination to treat the region as part of its core defence perimeter rather than a distant marsh.

Strategic and Diplomatic Outlook

Sir Creek’s importance extends beyond the boundary itself. Whoever controls it gains leverage over the maritime space between the Rann of Kutch and Karachi. For India, that means securing its ports, coastal infrastructure, and shipping lanes. For Pakistan, it offers forward visibility into Indian waters. The dispute also carries economic weight because the creek’s mouth opens into rich fishing areas used by communities on both sides. Hundreds of fishermen are arrested each year for crossing an invisible maritime line that still lacks formal demarcation.

Diplomatically, more than a dozen rounds of talks have been held since the late 1990s, but progress remains elusive. India advocates resolving the maritime boundary first using modern GPS and hydrographic surveys, while Pakistan insists the land boundary must be fixed before moving to sea delimitation. Domestic politics in both countries make compromise difficult.

For now, the region functions as a live frontier — quiet but heavily guarded, where soldiers, sailors, and fishermen coexist amid uncertainty. The build-up on both sides has introduced a delicate balance of deterrence. Any misjudgment could escalate quickly given the narrow waterways and the presence of armed patrols in close proximity.